Ullage is a great old British word referring to the ‘amount a vessel lacks in fullness’ or to put it another way how much is missing. In wine terms there should always be a degree of intentional and expected ullage as bottles are never completely filled. Even a newly-bottled wine should have a gap of around 1 or 2 centimetres between the bottom of the cork and the wine when standing upright. This both allows the wine to slowly mature and also prevents the cork from displacing (and therefore wasting) wine when it is first inserted into the bottle’s neck.

With significant bottle age, which can amount to decades, we would expect the level of ullage of a wine to increase even if it has been professionally stored in optimum conditions. As a general rule the older a bottle of wine is the more ullage one would anticipate. This is because corks absorb liquid and are permeable so miniscule amounts of wine are ‘lost’ in the process of long-term aging. Being fully cognisant of this well-established phenomenon the wine trade has developed a lexicon of terminology to accurately and helpfully describe the level of ullage in any given bottle.

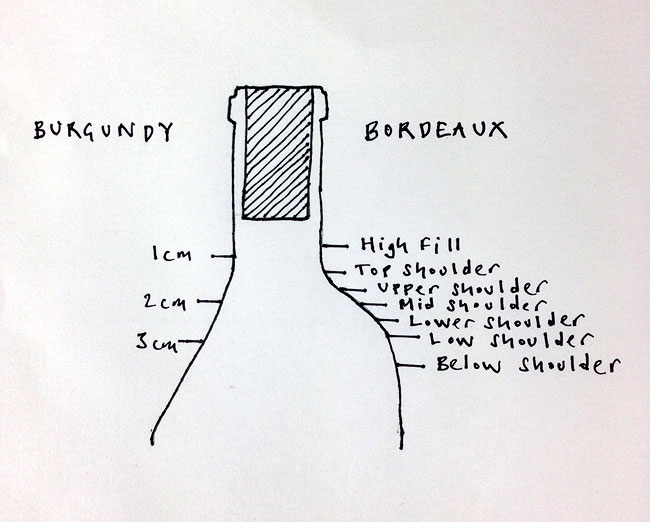

I could crash on at length here but there are times when it is best to resort to a diagram:

As you will see from my drawing Bordeaux bottles enjoy the more elaborate grading while Burgundy bottles, with their more sloping shoulders, tend to be judged simply in the metric distance between cork and liquid. In both instances the principle is the same though and the popular interpretation is the higher the level of the wine the ‘better’ condition the bottle is in. This is a sound starting point as badly stored wines will normally exhibit more or ‘worse’ ullage. That said, there are many variables here and different bottles of the same wine from the same case often exhibit markedly different levels of ullage. Unless I am buying fine, and therefore costly, wine whose provenance is not fully known to me, I tend not to get too hung up about fill levels and bottle variation. What I am always wary of are levels that are too good to be true. Bottles that have been reputedly aged for a quarter of a century or more with ‘perfect’ fill levels are always a cause for concern.

I’ve often enjoyed venerable old bottles that look to be in poor condition – it’s amazing how robust wine can be. Similarly a bottle that looks to be in terrific condition can still be badly corked or oxidised. Some illustrious Bordeaux Châteaux (including Lafite) and the celebrated Australian firm Penfolds have offered a ‘re-corking’ service whereby aged wines are topped up and re-corked and some official documentation is provided. Although I can readily understand the motivation to do this I am not a great advocate of the practice. I suppose it is fair enough if the client is fully intent on drinking the wine themselves but I think it is too invasive for bottles that are then going to be re-sold. As with cars, furniture and paintings it is best to see what you are buying in its original condition.

Pants!

Without a doubt the best way of ensuring your wine is in good nick is to buy it when it is released, from a reputable merchant, and cellar it yourself or pay for it to be professionally stored. That way you’ll know exactly what you are getting and there won’t be any short measures.

Pukka!